In common with the theme of this post, the form of this writing follows a meandering path. I have just returned from walking in the Scottish Highlands. The walk is a familiar theme in contemporary art[i], Long and Fulton are probably where one usually begins,

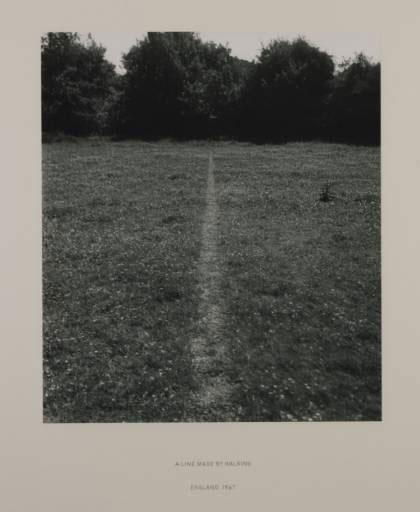

Long’s ‘A Line Made by Walking’ is the most straightforward and refers us, perhaps, backwards to the rural walk. For the urban walk there is the ‘dérive’ starting, arguably, with Guy Debord, looking backwards to the ‘flaneur’.

Edouard Manet: 'Music in the Tuileries Gardens', 1862. Oil on Canvas. 76 x 118 cm. National Gallery, London

(Manet’s self-portrait in the left corner of ‘Music in the Tuileries Gardens’, his monocle referring to Baudelaire’s original description of the term flaneur, Baudelaire is also amongst the painted throng), and forward, via Ron Herron’s ‘Walking City’ maybe, to pyscho-geography and Ian Sinclair[ii].

The Romantic Experience

I practise both, but standing on the top of Beinn Resipol,

the Romantic associations were uppermost, the line which runs from Keats: ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’, 1816

the Romantic associations were uppermost, the line which runs from Keats: ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’, 1816

“Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.”

The Wanderer (I roam around, around, around)

Or Caspar David Friedrich’s painting from a year or so later: ‘Wanderer above a Sea of Fog’, 1817 [iii].

Caspar David Friedrich: 'Wanderer Above the Sea Fog', oil on canvas, 98 x 74 cm, Kunstahalle, Hamburg.

Look at the ‘Wanderer’ carefully; the spatial construction makes the figure static and solid. It is directly on the central vertical axis

Caspar David Friedrich: 'Wanderer Above the Sea Fog', oil on canvas, 98 x 74 cm, Kunstahalle, Hamburg. Detail 1

and the waist on the horizontal,

the crag and head form a strong pyramidal structure.

the crag and head form a strong pyramidal structure.

Caspar David Friedrich: 'Wanderer Above the Sea Fog', oil on canvas, 98 x 74 cm, Kunstahalle, Hamburg. Detail 3

This pictorial strength, as it were, makes the wanderer a form of god in the way that he dominates the rest of the space, his Romantic imagination, and by extension, our own, creates the view. ‘The Wanderer’ is one of the first paintings in which we look with the figure from inside the painting, not at a painted figure looking at it. Friedrich takes the notion of the internal spectator and makes it the central focus of the painting, and makes that act of internal viewing the paradigm for all acts of viewing this side of the picture plane.

A Literary Device?

Powerful stuff, but to be honest it is a device and a literary one at that. We can see the apotheosis of experience on a mountain top. We can understand the analogous nature of viewer and internal viewers experience. But, there is very little particularity about what we are actually experiencing; it is a generic scene. It has none of the genuine nature of what it was really like to walk up there and stand above the clouds; cold and wet in my own experience.

‘Wanderlust’

As Rebecca Solnitt points out in ‘Wanderlust’, to walk is to be embodied. But is the figure in the Wanderer embodied, in the sense that it is corporeal and fully sensate? I think the precision of the co-ordinates that place it in pictorial space, militate against that reading. This is an intellectual body, a minds eye body, not someone who has toiled up through bog and slippery footholds, out of breath with the wind in their face, wondering which path to take. Can art ever present the embodied walker?

A better work on this theme was John Cale’s ‘Dreaming in Vertigo’ section of ‘Dark Days’,

shown at the Welsh Pavilion of the Venice Bienalle in 2009. If memory serves, he strapped a video camera to his chest and walked up endless steps on a Welsh hill. The soundtrack is of heavy panting as he struggles up a steep slope, the view is of a man working hard to keep walking.

Our Forbidden Land

The book of photographs by Fay Godwin: ‘Our Forbidden Land’, describes the real experience of a walk. The journey as a political tool is extended by showing the journey denied.

‘Our Forbidden Land’ is a series of polemical photographs taken around Britain, Godwin’s photographs of natural beauty show how ordinary walkers are denied access to that beauty. Over 87% of this country is privately owned, and another 13% is made up of roads and railways etc. A walker has only a one in three chance of being able to complete a 2 mile country walk along public rights of way. Her photograph of Glencoe in Scotland shows a dark tarmac road leading to the white mountains, the road is almost central, the diminishing single viewpoint perspective almost perfect, the snow on the mountains white and exciting, the sky clear, beauty in the wild. But the pressure of tourism in the area, the demand for new roads and the amount of rubbish thrown from passing cars speeding through Glencoe is horrible; this will destroy that beauty within the next few years.

So then, most images about walking tend to be making some other point, Christ striding about with a cross, fresh from the tomb off to have a few words with dad (‘Noli Me Tangere’). ‘Bonjour Monsieur Courbet’, the artist as The Wandering Jew, as the true seer of society. The group of walkers (the Bacchante) that meet the single walker (Ariadne) as she tries to call her lover Theseus as he sails away.

‘The Morning Walk’

Gainsborough’s ‘The Morning Walk’ might sum all this up.

Like ‘Mr and Mrs Robert Andrews’, it’s about ownership, walking the bounds of your property in your best shoes. Like the painting technique, this is a far more subtle painting than it’s predecessor, and infinitely grander. Compare the two dogs to get the sense of this change. The elegant white dog (a Spitz) versus the working gun dog; the dogs tell us who owns whom and what.

Dogs in Art

By the way, thinking of dogs in art have a look at ‘The Pont de l’Europe’ by Caillebotte,

the elegant hands behind the back, the swaying self-importance of the strolling flaneur. Notice the bustling dog though, which I have always thought stands as the internal urban viewer in this Realist/ Impressionist work.

The ownership theme is the same in both Gainsborough works, although the visual relationship between the white dog and the white dressed Mrs Hallet, makes her marital relationship to Mr H none too subtle.

The brushstrokes are the key to ‘The Morning Walk’; light, feathery, and gentle. The clothing was fashionable, not clothes worn for getting muddy on a long hike through real countryside. The delicacy of the paint matches the lightness of the walk through the grounds, they are on a well made path, the title is ‘The Morning Walk’, i.e. before the real business of the day. From the branches at the top left the eye is drawn to the pale background, then to the dog and back to the figures, the silks of the Mrs Hallet in particular. These light brushstrokes, made with a six foot brush, create serpentine movement, i.e. the type of movement expected for a gentle walk in one’s grounds, definitely not the earthy energetic rush of the hunter in Het Steen.

Our return from Beinn Resipol was neither gentle, nor light, it was definitely earthbound and very soggy; like all proper walks,

[i] I recommend this website on the theme as well: ‘Walking and Art’ a blog about the uses of walking in art

[ii] Might I mention here the existence of ‘The Suburban Hiking Association’ formed first in Leeds in the late 1970’s and then resuscitated with Adam Curtis and Mary Harron in Brixton in the middle Eighties. Us Suburban Hikers met in the centre of town and then travelled to the ends of tube lines to collect stories and characteristic objects to display to each other at the subsequent party.

[iii]I have fond memories of this painting, it was the cover of the second Mekons Album (from 1980 I think, memories of that period are a little vague).

Originally there was to be a speech bubble coming up from the fog below with “It’s De Mekonns Bas” written in it. We thought this would sum up the ironic contradictions between attacking Capitalism, yet using it’s mechanisms to create profit. Virgin Records, and then Rough Trade, hated the content, we really were outside the system now. Somewhere along the line the name changed to cultish references to pop fiction.