On the Platform

Waiting at the station, I talked to a man about cataract operations for Labradors, £3000 per eye apparently. It would be cheaper to send the dog to India he thought, but wasn’t sure about quarantine.

The bus to the station had to drive through thick fog, bright but visually impenetrable. Trees are just changes of tone in a wall of grey/ white, like the steam on glasses in a hot bathroom as you clean your teeth before departure.

Art about not seeing

It is rare to find art work that presents a restricted vision. Or, restricted vision as a deliberate theme. You could say that the late work of Monet and Degas, as they struggled with eyesight problems, are the results of restricted vision itself, but I’m not sure Claude or Edgar would thank you for it; not really what they were intending to do. Duchamp’s last work (Étants Donnés) perhaps, where we can only see through the holes in an old door. In most art your eye is directed around pictorial space, yet you are simultaneously aware of the whole work. Think of artist play with mirrors:

Velasquez’ ‘Rokeby Venus’, what we see in the mirror, (her face), is not what we (the male viewer) want to see, her naked front, although we know that the mirror is in fact pointed at that very form.

“Charlie ruined his IPad yesterday, he rebooted from a PC and it like, wiped all the applications, there is nothing to see, just the empty screen.”

“Why’d he do that then?”

“Don’t know, because he’s a boy? It was great”

What about ‘The Day of the Triffids’, those unable to see on the night of a meteor shower are saved from blindness. They survive deadly killer plants, ending up in the Isle of Wight of all places; is this a metaphor for enhanced perception? Perhaps not. Or the standard ‘blind so that he might really see’ trope (Homer, Gloucester in Lear, Milton etc.) I suppose it’s not surprising that an art work, an object to be seen, is made with visual clarity, and doesn’t concern itself with not being able to see. But art about how we perceive the world and how we see ourselves, there’s lots of that.

“Look, he sent me a text, says he wants a picture of me, not a dirty picture or nothing, just a nice one he can put it in bed at night and see me when he gets up in the morning”

“Nice”

“Yeah, right”

The schoolchildren are opposite, two women in front are discussing their day, they have documents on the table, ‘Rebranding HLC/ALCs: a New Look’, quiet speech in determined tones, lots more jargon.

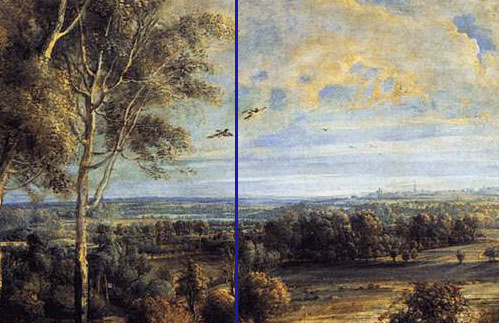

Peter Paul Rubens: 'A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning', 1636. Oil on Oak. 131 x 229.cm. National Gallery, London

In front of Het Steen

Behind me a large French youth is lying full length on the bench, earphones on and singing. Next to him, two equally disengaged young men, equally French; all are wearing sportsgear for the non sportif. They comment loudly on the girls that pass. They have yet to turn round and see the Judgements of Paris. I suspect their reaction would be similar to the primary school boys who have just passed, their hands over their mouths, pointing and giggling.

Peter Paul Rubens: 'A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning', 1636. Oil on Oak. 131 x 229.cm. National Gallery, London. Detail The Trees

The Trees

The small group of six trees in the foreground island, are reminiscent of a group of people, standing tall. The oak on the left proud and straight, the birches in the centre: lounging, and the birch on the right swaying gently.

I am surrounded by people standing – to look at the art – apart from the lolling French behind. Many viewers take the attitudes of the outer left and right trees. It is only the young in groups who lounge and lean. Do we take the attitude of that we look at? More noticeable when looking at standing figures perhaps, adopting the pose of the Arnolfinis; that sort of thing.

Peter Paul Rubens: 'Landscape with St George and the Dragon', 1630, oil on canvas. The Royal Collection

Pathetic Fallacy

The blasted tree in the ‘Landscape with St George’ now in Tate Britain reflects this sort of ‘pathetic fallacy’ approach, as incidentally do the trees in the later ‘Judgement of Paris’.

Those to the left, with the clouds generated by the Goddess of Discord are dark and distorted and forked, echoing the shapes of the Goddess. The tree around which Hermes and Paris and their bovine dog are wrapped, is clean limbed and brightly lit.

Peter Paul Rubens: 'A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning', 1636. Oil on Oak. 131 x 229.cm. National Gallery, London

The scale of the trees in Het Steen really does not fit the figures. Judging from their foliage and form these are mature trees. Yet, stood beside them, the carter or his passenger would reach about half way up the trunk; implausible.

The Tree Question

Is it possible to be a self-conscious painted tree, a form that draws attention to itself? A question that is not quite as footling as it sounds. Such a question assumes that painted forms in their painted world have mass and agency within that illusory space. A world in which the usual laws of physics, those from our side of the picture plane, still operate.

Perhaps other human traits also apply, the jeunesse dorée behind me clearly believe they are objects of interest. They have positioned themselves and behave to draw attention; admiring attention they assume. I do not share their opinion, but I am in the minority. Their belief, to watch the huge numbers of European and British young moving through the gallery, is shared.

I wonder if the similarity I see between the composition of the trees and their anthropomorphic nature, comes from proximity. Apart from upright humans standing in front of them, they are flanked by triads of painted standing, naked women. Three goddesses confident in their nudity, conscious of being seen by Paris and Hermes, but not perhaps by us the viewers, or by aggressive young Frenchmen or giggling London primary schoolchildren. Is it possible to ask the question: are the trees in Het Steen aware that they are being watched, without putting my hand over my mouth and giggling?

The Tree Question: Context

The tree question presumes that we read a single standing form as part of a history of single standing forms. Rubens was a classicist, he would have known both something about Greek and Roman statuary and Vitruvius’ descriptions of the classical column as different forms of human figure.

Here, in these trees we have everything from Doric (the sturdy ‘male’ Oak) through Ionic (the curving birch as a young slender and female) through to Corinthian (The swaying birch on the right as the fuller female figure). John Summerson’s ‘The Classical Language of Architecture’, (Thames and Hudson) is very useful on all this by the way. Rubens would also have been aware of the general belief that Classical stone architecture was derived from wooden building techniques; we are looking at the painting of a building after all.

The Tree Question: Nonsense

But, of course this is all fanciful. The building is Flemish vernacular, look at the stepped gables,

Peter Paul Rubens: 'A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning', 1636. Oil on Oak. 131 x 229.cm. National Gallery, London. Detail Het Steen itself

the only classical references are textual; to Virgil and Horace. The trees are, as I have established earlier, just stock trees from the painters studio repertoire, no reference to anthropomorphism here at all.

More French youth have appeared, an army of them, enough to stock a re-enactment of Delacroix’s ‘Liberty Storming the Barricades’ though without the bare breasted Liberty, much to the disappointment of those on the bench behind. Like Delacroix’s painting the young folk around me are also stock characters, gum chewing, unshaven, louche and aggressive, time to go.