Het Steen, National Gallery, London, Friday Afternoon

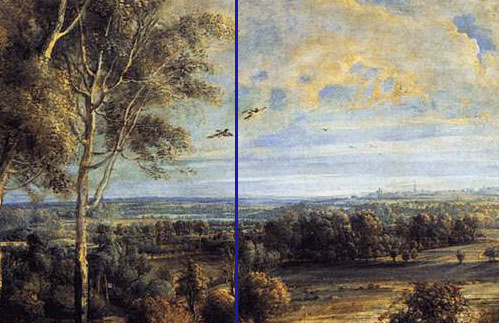

Peter Paul Rubens: 'A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning', 1636. Oil on Oak. 131 x 229.cm. National Gallery, London

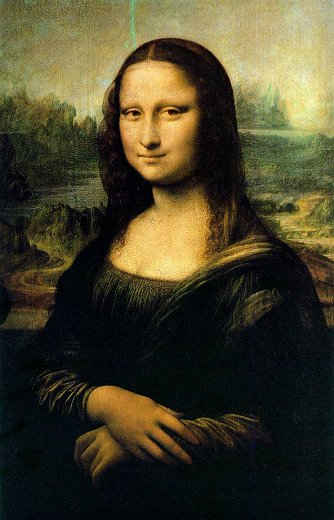

The young woman in front of the later ‘Judgement of Paris’ is haranguing a large group of fellow Chinese. She has talked for 10 – 15 minutes without drawing breath, a small boy has his hand up; he is ignored. She is wearing cream trousers and a cream jacket zipped right up the neck, she does not look relaxed.

A complete contrast to a colleague I saw this morning, taking a large group of Year Eight students through a range of paintings about rooms and interiors: Dutch and Swedish ending with Rachel Whiteread. It was all about interaction, questioning, and the students lively responses.

How Do We See Art?

Returning to the central theme of all these posts: how do we see art, what do we get from looking at it? The students in front of the slide show had been led by careful pointed questions, what can we see? What might be the relevance of? What does that make you think about? The importance of composition/ light/ context/ new ideas about interiors. But I wondered, were they just showing their skills at a particular game: answering questions (very high) or were they actually engaging with images. Was this the equivalent of twenty questions, just running around a museum pressing buttons. Their teacher by the way was wearing dressed down art teacher clothing; checked shirt and jeans.

Pictorial Space

I think these posts have established by now, that composition of pictorial space has a great deal to do with how a painting is approached; physically and mentally. But, schooled in iconographic analysis or not, you also bring assumptions about behaviour and meaning on the far side of the picture plane. For example, I remember a small boy’s response to Picasso’s ‘Woman Weeping’

‘I know she’s really upset’

‘Why do you know that Darren, is it to do with the shapes clashing together in the painting?’

‘No, it’s because she’s eating pizza, my mum always gives me pizza when I’m upset’

So, what do we bring to Het Steen? A general assumption about the reassuring properties of paintings about nature? A deep calm, from the gently lifting ground plane, the soft, close tonal range, the warmth of colours in the foreground, the bucolic carter and companion, the wealthy but not obtrusive house? Soft shapes rising sun: optimistic; reassuring; comforting. These are the sorts of terms that come to mind. It might be autumn, i.e. towards the end of a cycle, but time moves very slowly here.

Large numbers of Spaniards, smelling rather strongly of soap, not unpleasant but certainly insistent, are collapsed around the bench. It is a comfortable place to rest, they are exhausted, time this side of the picture plane is catching up with them. At the other end of the bench, a man is slowly making an extremely painstaking tonal drawing of the later Judgement; hours of evident labour. He is drawing from left to right and the proportions are gently getting away from him; the figures are beginning to elongate and lose their Rubensian plumpness as the drawing becomes widescreen.

The Spanish, distressed brown leather, sports gear and strange white tubular headgear rather like socks, do not look at the paintings. Later a middle aged English couple, beige trousers, grey anoraks, argue in a low monotone, carefully looking at an image, true; but it is a tube map. Most of the visitors, few are actually viewers, seem to regard being here as a form of labour, measured in miles walked, the occasional interesting painting is a bonus.

The ‘Art Study’ Problem

Perhaps this is behaviour learnt early. By and large students coming into an art room see making art as a subdivision of leisure activities; ‘Art’ is not real work etc. Whereas looking at art made by others is always more of a chore, any art teacher who has tackled the ‘art study’ will confirm this. I have written many books for teachers trying to overcome this reluctance, but never quite worked out why it is there; surely pictorial space is fascinating, isn’t it?

But What Shall I Wear?

Maybe it is to do with clothing, to make art in an art room you put on an overall, a paint spattered ‘cloak of creativity’ as it were. To study the art work made by others you are still in the clothes you wear for other activities, learning Maths for schoolchildren, travelling seems to be the main theme here in the National Gallery. I don’t mean that you should stand in front of Het Steen wearing seventeenth century muddy peasant linen bowing to the Lord of the Manor, but the awkward mismatch between formality and casual tourism is noticeable. At the Damien Hirst exhibition at Tate Modern, that I saw earlier (highly recommended by the way, very well put together indeed) there was none of that awkwardness; art and viewers seemed to be well matched. So perhaps it does help to dress accordingly, I’m off to order my rough smock now.