The Paradox of Apparent Movement

Stuck, unable to go anywhere, waiting for a train, I was thinking about our acceptance that a painted image contains movement. Why, when looking at that static image do we: happily predict what will happen next; what has happened before and what, from analysis of that movement, is the mental state, ideological position and historical context of all involved? Do we like looking at paintings because there is a comforting pleasure in knowing, or working out, what will happen next? Or perhaps when looking at a landscape painting, knowing that nothing will happen next, that we are in a comforting world of ‘not going anywhere’?

“My cousin right, she wants to go to Tenerife to swim with Dolphins”

“Oh, I don’t fancy that, they’re big fish. No, I couldn’t do that. I want to go to Australia”

“What, and swim with Aboriginals?”

The Story in the Object

Viewers in the National Gallery, London, seem more interested in the story of the object, than the story in the object; is that because these stories have been lost? Look, for example at Caravaggio’s ‘Supper at Emmaus’, 1601, the earlier one in the National.

At the centre of a shallow rectangular pictorial space, a young man gestures meaningfully with his right hand and waves his left over a loaf of bread. To his left an older man symmetrically stretches out his arms. Above the young man to his right, another man stands, casting a circular shadow over that younger seated one. Nearest to us, in the left foreground, a man with a hole in the elbow of his jacket pushes his arms down onto the arms of his chair, as if to lift his body upwards.

Good Lord, it’s You!

The original sixteenth century viewers of this painting would have recognised the story, and known that it is about sudden recognition. It is in the bringing together of the gestures: with the immediate story; with the past that led these figures up to this point; with the subsequent future affecting us all, that this painting extends the movement beyond what we immediately see. That bringing together, or conjunction, leads us back to the dusty road en route to Emmaus and the inn where the painted action happens. On that road the older, seated men had met the younger, discussed the recent crucifixion of Christ in Jerusalem, and the disappearance of his body from the tomb and the appearance of angels saying that he was alive. They persuade the, as yet unknown, younger man to eat with them.

“30. And it came to pass, as he sat at meat with them, he took bread, and blessed it, and brake, and gave to them.

31. And their eyes were opened, and they knew him….

35. And they told what things were done in the way, and how he was known of them in the breaking of bread.

36. And as they thus spake, Jesus himself stood in the midst of them, and saith unto them, Peace be unto you”

Luke 24. 30-36.

The Significant Gesture

They (Cleopas and possibly Peter, possibly James) recognize the resurrected leader of their group (Christ) through one of the last gestures that they saw him make (breaking bread at the Last Supper).

Caravaggio: ‘The Supper at Emmaus’, 1601, 141 x 196 cm, oil on canvas. National Gallery, London. Detail: Christ’s gesture.

The actual last gesture, as it were, that they saw him make is reflected in the outstretched arms of the right hand disciple: the crucifixion.

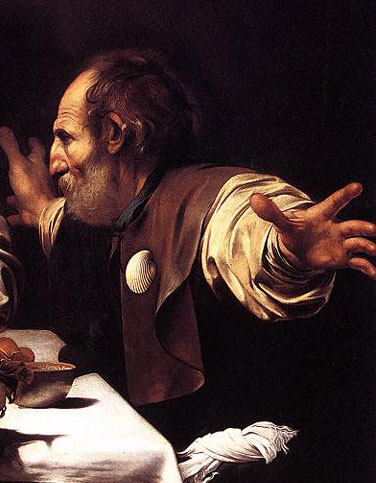

Caravaggio: ‘The Supper at Emmaus’; 1601, 141 x 196 cm, oil on canvas. The National Gallery, London. Detail: Disciple with arms outstretched.

I suppose you could call this conjunction; potentialities. There is a range of those potentialities, the striding movement of walking for example, and don’t these worn, sunburnt and slightly battered figures look like they have done a lot of walking in their lives. Notice by the way the cockleshell on the leather jerkin, the symbol of the pilgrim, the walker. The significant, human movements that pinpoint or focus, key points of the story. Notice also that those gestures scoop in the viewer, draw us into the heart of the story.

“I’m not going nowhere because I literally can’t walk no more than, like, one mile an hour”

“Like, I can’t even do that”

Viewpoint

Viewpoint is always crucial in a painting, where are we the viewer situated by the artist’s construction of the pictorial space? In this case, we are below the head of Christ, at roughly the same level of the two disciples. Although we are not close up to the table, that viewpoint is certainly from someone seated in front of Christ, drawn into his circle. The vigour of the painted gestures demands that the viewer makes equivalent movement this side of the picture plane, in our own recognition of the story and its importance.

I have just remembered, thinking back to earlier posts about what we as viewers bring to our viewing position. A boy once told me that this painting was all about telling lies and fishing:

‘You see that bloke on the right Sir, well he’s telling the others that he caught a fish and it was thiiiiis big (boy stretches out his arms in imitation) and the others Sir, well you can tell they don’t believe him”

Hurry Up and Wait

I wrote part of this waiting for my train, in the ticket area of the station. A rectangular area, parallel to the tracks. At one end: ticket sales, here the endless complexities of ticket types are negotiated. At the other: a newsagent, usually shut. Doors on each long side exactly bisect the space. These doors are automatic, over sensitive sensors open them unexpectedly and violently with an uncontrolled shake at their full extent. The track faces due north, the prevailing wind is westerly. Each time the doors suddenly fling themselves open, the wind charges through as though it is late for the fast train to London Bridge.

On each of the four benches, like points of the compass, are static middle aged men:

-

To the North West, one in brown cords and shoes, green socks and light blue striped shirt, blue jacket and bright orange Apple laptop.

-

To the North East, another, in grey suit, white shirt, pale grey tie, permanently speaking on a black shiny mobile.

-

South East, in a charcoal suit, cream shirt, black bag on lap, reading white A4 documents.

-

And me at South West, all in black with a black A5 notebook.

We are all waiting, our gestures are subdued, our composition is precise, and appropriately measured for the subject.

The Composition of Pictorial Space

Figures in pictorial space are often symmetrically arranged, usually about a central axis, ie placing the viewer directly in front of them. Think of Egg’s Travellers, that I have mentioned before,

Augustus Leopold Egg: ‘The Travelling Companions’, 1862 oil on panel. 65 x 79 cm. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

that overt symmetricality has meaning, as does the lack of precise composition in Veronese’s: ‘Christ Healing a Woman with an Issue of Blood’ .

Paolo Veronese: ‘Christ Healing a Woman with an Issue of Blood?’, 1548, oil on canvas 117 x 163 cm National Gallery, London

In Supper at Emmaus the viewing point would seem to be directly in front and significantly below the normal eye level so that the vanitas bowl of fruit on the lip of the table appears to be falling on top of you.

Caravaggio: ‘Supper at Emmaus’; 1601, 141 x 196 cm, oil on canvas. National Gallery, London. Detail: Fruit Bowl.

The light in my waiting room is even and clear as fits the scene, but in Caravaggio’s inn, some three days walk from Jerusalem, the light is stark: bright highlights; pools of meaningful darkness; the shadow/ halo around Christ’s head; the darkness of the tomb from which he has risen.

A well dressed couple pass through from west to east, I just catch the end of their conversation:

“We’ve got enough for the moment, we’ve got the six nuns in Peterborough”

Unlike the vigorous painted gestures, our bodily movements in the ticket area remain subdued, slow and undemonstrative. We are not going anywhere, no dramatic revelations of redemption here.

“South Eastern Trains would like to apologise for the delay to your service this morning, this is due to the late running of the train”